My father shoved my nine-year-old daughter out of her chair halfway through Christmas dinner, and the sound of her body hitting the hardwood was quieter than the silence that followed.

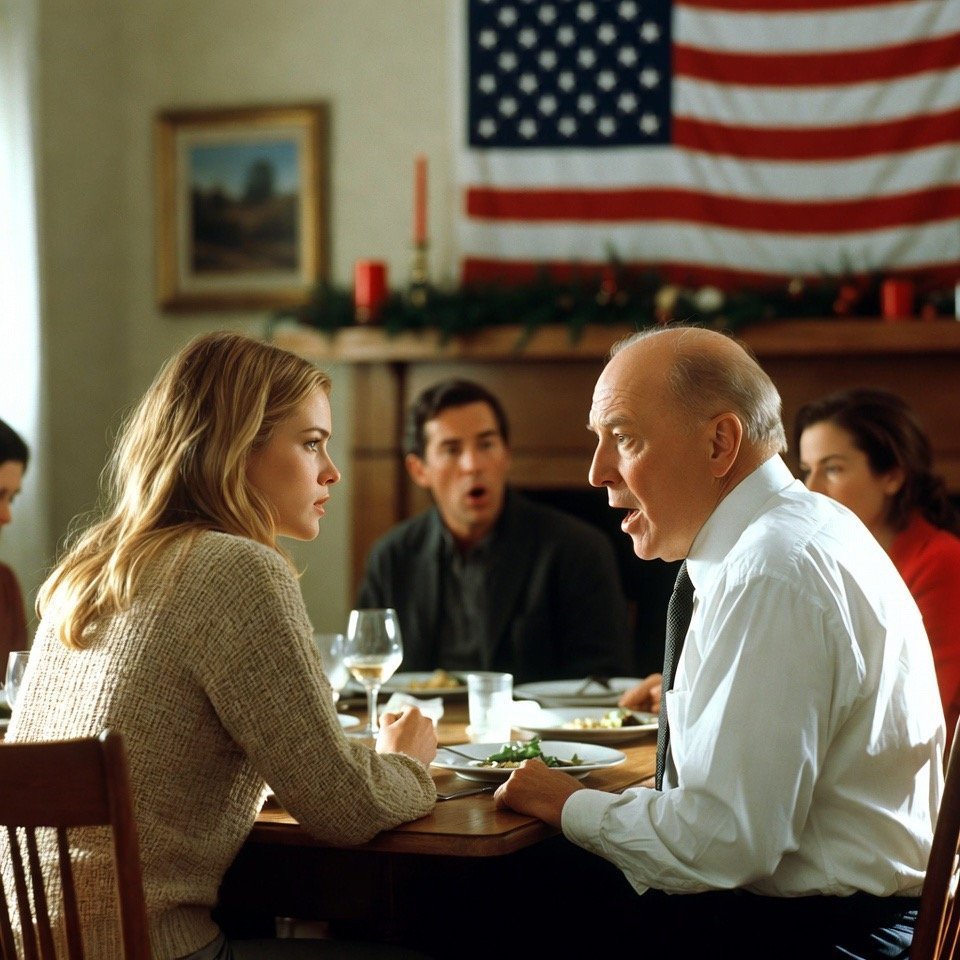

Twenty people sat around my parents’ farmhouse table, the good china out, the centerpiece of holly and candles arranged just so, the smell of rosemary and ham floating over everything like it was a normal night. Outside, snow pressed up against the windows of their colonial in Westchester County, New York, soft and postcard-perfect.

Inside, my father’s hand slammed into Lily’s small shoulder.

“That seat is for my real grandkid,” he snapped. “Get out.”

Her chair slid back and tipped, legs screeching on the floor before it went over.

Lily’s knees hit first, then her palms, a dull thud of nine-year-old bones meeting polished oak.

Her breath left her in a short, shocked gasp. A fork clinked against a plate.

A napkin drifted off someone’s lap.

No one moved.

My mother sat closest to her, fingers still wrapped around the stem of her wineglass. My sister Olivia froze with her phone halfway back into her clutch.

My father kept his fork suspended in midair like he was waiting for someone to hit play again.

Lily looked up at me from the floor.

Her eyes were wide and completely dry, like her body hadn’t gotten the message yet that this was supposed to hurt.

That was the moment something inside me stopped trying to make sense of these people.

I pushed back my chair. The scrape of wood against wood was louder than her fall. My father flinched at that, at the noise, not at his granddaughter on the floor.

It told me everything I needed to know.

I crossed the room and knelt beside Lily.

Up close I could see the skin already reddening beneath her tights, the faint tremor in her hands.

She grabbed my sleeve like the ground might tilt again.

“I’ve got you,” I whispered, my voice low enough that only she could hear. “I’ve got you, baby.”

She nodded once, quick, the way kids do when they’re trying very hard not to cry.

I helped her to her feet, one hand under her elbow, the other steady on her back. She folded herself small beside me, like taking up less space might make her less of a target.

I waited three heartbeats.

My mother stared determinedly at the cranberry sauce.

Olivia’s gaze flicked from her daughter Emma to Lily as if she were weighing which reaction would cost her the least.

A cousin studied the centerpiece like it had started singing. Someone cleared their throat. No one said a word.

My father finally exhaled.

“She shouldn’t have been in that chair,” he said, like he was correcting flatware placement.

“That place is for family.”

Family.

The word landed heavy and sour.

I straightened, keeping Lily tucked against my side.

My fingers found the strap of my bag on the back of my chair. The leather was familiar and grounding, pressing into my palm like a reminder.

I’d told myself I was waiting until after the holidays.

I wasn’t waiting anymore.

My mother’s eyes snapped up the second I lifted the bag.

“Hannah,” she said quickly, too quickly.

“Don’t make a scene. It’s Christmas.”

I almost laughed.

Instead, I walked to my end of the table and set my bag down, right between the gravy boat and the platter of rolls.

I unzipped it slowly, the sound loud in the thick quiet, and slid out a plain, unmarked folder.

The folder had lived in that bag for a week.

Tonight was the third time it had sat on this table. The first two, I’d left it closed.

Not this time.

I placed it directly in front of my parents, squarely between my father’s plate and my mother’s wineglass.

“You don’t get to touch her,” I said, my voice calm in a way that surprised even me. “Not ever again.”

My father’s jaw tightened.

“Don’t be dramatic.”

I looked him in the eye, the same pale blue I’d stared at my whole life and never quite believed.

Then I said the four words I’d only ever rehearsed in my head.

“You’ve been served, Dad.”

For a second, nothing happened.

The room was all breath and heat and the faint ding of some timer in the kitchen.

Then my mother’s wineglass slipped from her fingers.

It hit the table with a sharp clink, red liquid sloshing dangerously close to the folder before tipping over, staining the white tablecloth in a spreading bloom the color of someone else’s heart.

—

The thing about breaking points is they never really appear out of nowhere.

People like to pretend they do. It makes it easier to act shocked.

“Oh, she just snapped,” they’ll say, like the last straw wasn’t stacked on top of thousands of carefully placed ones.

It didn’t start with my father knocking my child to the floor.

It started in all the small ways they told me who I was.

Growing up in that house in Westchester, Olivia was sunshine and I was static.

That was the family joke. Olivia walked into a room and compliments followed like confetti.

She got “Look at you!” and “You’re glowing!” and “Sit by me.”

I got “Move, you’re in the way.”

When Olivia was five and smeared chocolate cake on the wallpaper, my mother laughed and dabbed at the stain.

“She’s spirited,” she said fondly.

When I, at seven, knocked over the same vase by breathing too close to it, my father shook his head and muttered loud enough for everyone to hear, “She breaks everything she touches.”

If he laughed while he said it, it didn’t count as cruel.

If everyone else laughed with him, it became the truth.

I learned early that in our house, tone mattered more than impact.

I also learned there were things we didn’t talk about.

The first time I heard my own existence questioned, I was fifteen and eavesdropping without meaning to. Thanksgiving, the whole extended family crammed into the same house that, years later, would host the Christmas where Lily hit the floor.

I was in the hallway, halfway to the bathroom, when I heard my aunt’s voice float from the dining room.

“She doesn’t really look like Richard, does she?”

A beat. Then my father’s familiar chuckle.

“Well, every family’s got its mysteries.”

Laughter followed, warm and easy.

No one stepped into the hall to see if I’d heard.

No one came to find me in the bathroom, where I stared at my own reflection and tried to figure out which parts of my face didn’t belong.

My mother never corrected him.

That was her talent—smoothing napkins over messes and changing the subject.

If cruelty was his sport, silence was her strategy.

I didn’t have proof of anything, just whispers and offhand comments and the way my father’s eyes sharpened around me when he’d had a little too much to drink. I told myself I was imagining it.

Then my grandfather died.

My father’s father, the only person in that house who treated me like I wasn’t a mistake someone forgot to erase.

He wasn’t warm.

He didn’t hug. He wasn’t the grandpa who slipped you candy or told you bedtime stories.

But he’d pat my shoulder when I walked by and say, “You’re sharp, kid.

Don’t let anyone dull that.”

He left behind a quiet grief and a louder shift in power.

After the funeral, the papers came out.

Not in front of me, of course. I was twenty-three, the age where you’re considered old enough to work two jobs but too young to be trusted with a pen.

I watched from the kitchen while my father and Olivia disappeared into his office with an attorney and a stack of folders. My mother told me it was “just boring paperwork.”

When I finally got up the nerve to ask if my grandfather had set anything aside for me—a small cushion, a bit of help to get out of my unsafe basement apartment after a break-in—my mother didn’t look up from rinsing dishes.

“There wasn’t anything,” she said, her voice flat as running water.

I believed her.

At least, I tried to.

Believing her meant my father’s endless jokes and small cruelties were just personality, not strategy.

Believing her meant I wasn’t being stolen from on paper and in person.

The alternative was worse: that they could look straight at me and choose to lie.

Years blurred into each other.

I met Lily’s dad during a stretch of time when I was working nights at a hospital registration desk and grabbing breakfast at a diner near the Metro-North station. He was a paramedic on the night shift, kind in the way tired people are when they’ve seen too much.

We were together long enough to have Lily and to realize we weren’t good together.

He moved to Denver when she was two. He